As I mentioned in my previous post about north-east goldfields, the town of Mangana, under its older name ‘The Nook’, and the Tullochgorum Estate next to it are generally credited as the first official discovery of Tasmanian gold. Was there more to the story?

Tasmanian gold

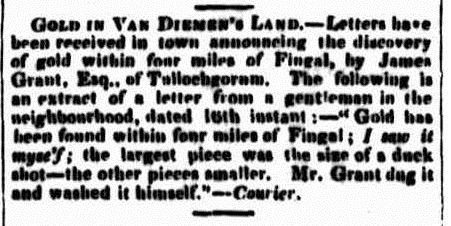

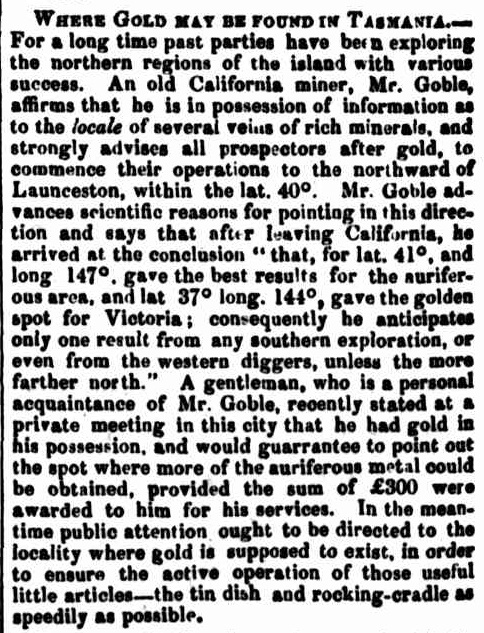

With these words, the Launceston Examiner reported what is officially recorded as the first discovery of gold in the State, on the 18 February 1852. But was it as simple as that? Was Mangana, in the summer of 1851/52, really the first discovery of Tasmanian gold? Rumours of gold discoveries had been circulating for some time. Indeed only four months previously, on 18 October 1852, the Hobart Courier reports a meeting held to organise a reward for the discovery of gold in the colony, and particular areas of north-eastern Tasmania were being recommended as promising to would-be prospectors. Not that all such recommendations appeared very sound, as this pearler in the Colonial Times on 28 November 1851 shows:

Sounds like divining at it’s finest, if you can make more sense of that than I can, please let me know! Still, the implication from the first sentence is that some people at least were having some success in the search for gold.

It is difficult to be sure whether gold was known with certainty from Tasmania before this, but articles like the one I just cited seem to imply that it was. Several people claimed to be the first discoverers of Tasmanian gold before the Mangana discovery, and two of these stand out: Ferdinand Riva, a German jeweller from Launceston, who is reputed to have found gold at either The Den or Nine Mile Springs (Lefroy) in either 1847 or 1849, depending on what source you look at, and John Gardiner, who is reported to have dug up gold while working at Gilbert Blythe’s limeworks, in Beaconsfield, in 1847. He is stated to not have recognised the gold for what it was, and he eventually moved to Victoria. Of these only John Gardiner is credited in authoritative modern publications, such as the fairly recent Tasmanian Geological Survey Record 2013/10. Riva is mentioned many times in the press and on various modern sources on the Internet, but I’ve only been able to find articles giving him credit from well after the reputed discovery, so it’s difficult to know for sure. In contrast, while John Gardiner’s find only saw the light 22 years after the fact, there are contemporary news reports of his involvement with a Launceston prospecting association in 1869. According to The Examiner he offered to take prospectors to his original find of 1847. After working in the Victorian goldfields he had learned the significance of his earlier find, but when he returned in 1869 his original workings could not be found. The scheme apparently fell apart, but he evidently wasn’t totally making it up: the search caused prospecting interest in the area to pick right up, and eventually led to the discovery of the Tasmania Mine in Beaconsfield, the largest gold mine in the history of this State.

Was gold discovered in Tasmania even earlier than this? It had been found in other Australian States earlier than the main 1850s rush, but the Government of the day wasn’t keen to publicise the fact. Maybe they feared unrest among the convicts, and labour was very much in short supply at the time. The Government was afraid of people giving up their jobs in search of gold, with an already bad labour shortage.

What changed in the lead-up to the Mangana discovery?

Why was there no hindrance to the publication of the Mangana discovery in 1852, when news of other discoveries had so far been suppressed? What had changed to make the Government, previously fearful of losing labour to the gold rushes, change its mind? The most common theory blames the discovery of the biggest gold rushes of the 19th century, first the goldfields of California, and then Victoria and New South Wales. Up until this time, Australia was relying on steady immigration and convict labour to supply workers. From the first settlement, there had been an almost chronic shortage of labout, and by the 1850s the end of transportation was in sight. Reports of fantastic new gold discoveries, first in California and then in other Australian colonies, were in the local press almost daily, and more and more Tasmanians were deserting their jobs to go off to the gold rushes in search of their fortune. Colonists were being positively bombarded with headlines about fabulous gold discoveries:

- 1848 headline

- 1849 headline

- 1849 headline

- 1849 headline

- 1851 headline

- 1851 headline

The acute labour shortage was becoming even more dire as a result of the mass emigration, to the extent that by 1852 a local Tasmanian gold rush was probably viewed as desirable, as it would keep able-bodied workers in the colony, and possibly attract outsiders to come and work here.

Interestingly, the find at Mangana was originally subject to a great deal of skepticism. Several reports and letters to colonial papers of the time spout the point of view that the amount of gold to be found was insignificant and that digging for gold was a waste of time and useful labour.

The Government, still perhaps paranoid about losing workers or a deteriorating law and order situation, quickly moved to regulate the diggings. On the 5th of April, the Governor William Denison issued a proclamation making it illegal to look for gold without due authorisation.

Nevertheless, most of the gullies surrounding the township were eventually worked for gold, with Majors, Calders, Sharkeys, and Sailors gullies being the main producers. Estimates vary, but it seems that something in the order of 5,000–15,000 ounces of alluvial gold were produced, and most of that in Majors Gully. By 1856 attention was turning to reef mining, and a promising discovery was reported by The Courier (Hobart) on 8 July on Specimen Hill, just above the original township. In 1859 the Sovereign mine opened, the first hard-rock gold mine in Tasmania.

Within a few short years of the Mangana discovery, many of the main Tasmanian gold fields, except for those on the west coast, had been found, and the industry mining for hard-rock gold, and eventually for silver and tin, would bring to Tasmania an unprecedented (and still unrepeated) period of economic prosperity.

Mangana today

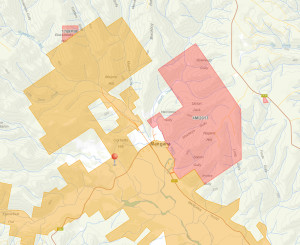

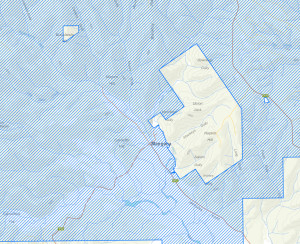

If you want to fossick aroung Mangana, it’s not an easy task. Much of the land is private property, having been sold before the Government implemented a policy of not selling mineral lands, so you’ll need to organise permission to access. There are numerous titles, and it can be difficult to know who owns what. On top of this, the most productive gullies on the northeast side of town are inside a current mining lease, and pretty much all the rest in a current exploration licence. I’ve heard a few people say that permission for prospecting in the exploration licence has been hard to get. Here are some graphics to illustrate:

- Mangana private property (LISTmap)

- Mangana exploration (MRTmap)

You can use LISTmap or MRTmap to overlay active mining tenements over the maps of Tasmania (you can see how to do this in a video here), which is what I did for the pictures above. Through that you can find the tenement owners and ask for permission, though I have heard it can be hard to get. If you do get refused by any mining company to access an exploration licence area, remember that the law (MRDA 1995, Section 112.4) entitles you to get reasons for the refusal in writing. I think Mangana is unfortunately in or near the ‘too hard basket’ at the moment, so it might be better to target areas where permission is not so difficult to obtain.

Newspaper articles were found in Trove reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Australia. This is a very useful resource to search in old newspaper reports about the area, and it’s how I came across the articles I’ve presented here. Other than that there are some publications about Mangana in the Mineral Resources Tasmania online library. There are many old exploration company reports, as well as proper publications. Among the proper publications, the ones I’ve found the most useful are:

- ‘The Mangana Goldfield’, W.H. Twelvetrees (1907).

- ‘The Mangana Goldfield and adjacent gold mining areas’, R.S. Bottrill (1992).

- ‘A summary of the Tower Hill, Mathinna and Dans Rivulet Goldfields’, J. Taheri & R.H. Findlay (1992)

If you have any areas in or around Mangana that you’ve found good, and you don’t mind sharing, then please leave a comment!

Do you want to know more about this? Perhaps there’s a topic on Tasmanian mining history (or anything else) you’d like me to write about? If you like the content at Apple Isle Prospector, feel free to get in contact, or leave a comment.