This is an article published in the Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette (Queenstown, Tas. : 1896 – 1902), Saturday 28 November 1896, page 3. I have a separate page with more information on the goldfields around Queenstown in general.

THE DISCOVERY OF MOUNT LYELL

THE INCIDENTS THAT LED TO IT

(BY ONE OF THE PROSPECTORS)

The Heemskirk tin field, situate at Mount Heemskirk, on the west coast of Tasmania, distant from the present township of Strahan twenty miles, will be remembered by many, both in Victoria and Tasmania, who were unfortunate enough to invest their money there.

From slight causes, easily forgotten, often spring most important results, and my object in alluding to Heemskirk is that it was the direct cause of Mr. F. O. Henry establishing a store at Macquarie Harbour (on the site of old Strahan), which afterwards served as a base for the operations of the prospector.

In the latter part of the year 1882, or early 1883, a Mr. Con. Lynch arrived in Macquarie Harbour, in charge of a party of prospectors, to prospect for gold, in the interests of a Hobart syndicate.

He left Kelly’s Basin, in the Harbour, and struck for the gap between Mount Sorell and Mount Darwin. Through the gap he went, and emerged on a level piece of country called Flanagan’s Flat, which has for many years been worked for alluvial gold, and is even now being worked by several parties, including Goring and Edwards, Glover, Gilbert, and Jones. Lynch crossed the head of the flat and carried his track to the Garfield River. Tom Currie was with Lynch, in charge of the track-cutting, Lynch following up, prospecting the country en route. After crossing the Garfield, into which Flanagan’s Creek flows, a river that rises in the foothills of Mt Jukes and Mount Darwin was reached. This was christened the Currie River. The party followed it down for about three miles and then made for the King River, which was crossed at the opening of the second gorge, near where Harris’s Reward claim is situated. The course of the King was followed to the confluence of the Queen, a few chains up from the place of crossing. The party then kept to the Queen, following its course for about six miles, till they came to a creek, which was called after Lynch, and is still known an Lynch’s Creek. Here Lynch discovered gold and the Hobart syndicate being advised of the find, was formed into the King River Company. [The difficulties of the route from old Strahan, and the story of how the King River first came to be navigated, will be discussed next week.—ED.] What these sturdy pioneers went through is easy to depict. But what would the brave men of those days not do? They regarded the forces of nature simply as obstacles to be overcome. Nothing seemed to daunt them. The golden magnet was drawing them on, and that was enough to make manly men intrepid adventurers. Thousands today owe them a debt of gratitude for their boldness in opening up this rugged and difficult country, whose treasures were so well hidden.

In the year 1880, or 1881, gold was discovered by Mr. H. Middleton at Middleton’s Creek, Pieman River, about fifty miles to the north of Macquarie Harbour. [The Merediths, who were the mining pioneers of the West Coast, claim to have discovered gold on the Pieman in 1877.—ED.] The Pieman Rush, as it was called, brought many experienced men from the various colonies to the West Coast, but the gold obtained was not commensurate with the difficulties and hardships to be surmounted and endured, and as a consequence, when Lynch’s discovery was reported, the Pieman was almost entirely deserted in favour of the new field.

Lynch’s Creek by no means proved the Eldorado expected, and if the difficulties of the Pieman were bad, the difficulties of Lynch’s Creek were fifty times worse. On the Pieman, men had not to pack supplies more than five or six miles at most, and the tracks were comparatively open; whereas at Lynch’s Creek Lynch’s original route had to adhered to. This meant a boat voyage across an arm of Macquarie Harbour to the entrance to King River, then a pull up that river to the rapids, after which all hands had to jump out, often up to their necks in water, and haul the boat over rapid after rapid in quick succession, and this for fully three miles, until the top landing—Lynch’s original depot has since been known as the the top landing on the King—was reached. Here the contents of the boat were put up in packs; these were mounted on the men’s backs, and thus the sturdy pioneers proceeded with them to their destination (Lynch’s Creek), even to nine miles distant, by means of a track which was no better than a badly blazed line through ugly scrub and over broken country.

One trip was quite sufficient for the majority of the men, especially as the creek was poor in gold, the result, being that most of them cleared, cursing their luck, the prospector of Lynch’s Creek, and the Country generally.

There were, however, some dauntless miners on the field who liked the country from a mineral point of view, and who looked upon it as one of great possibilities, and although the drawbacks were enough to damp the ardour of the most inveterate Irishman, and to make the most resolute man pause, they determined to have at least one more try, in a new direction, before finally abandoning the country.

With this object in view, a party consisting of Harry Everett, Howard, Healy (since dead), and one or two others, left old Strahan, and alter pulling across Long Bay, started for a distant range of mountains, bearing from them about north-east. They kept this bearing as near as the inequalities of the country and the close nature of the undergrowth would permit, prospecting every likely place they came to, until at length they emerged on an open plain (which was named Howard’s Plain, after Howard, one of the party, and which name it still retains), distant about 15 miles from the present township of Strahan.

Crossing this open country in a direct line for the mountains Owen and Lyell, which were now in full view, not being more than six miles distant bearing east, they found themselves on the western fall of a large stream. This stream proved to be the Queen River. They discovered payable gold in a creek, which was afterwards known as Howard’s Creek, and subsequently a second payable creek was found, which was named Lynch’s Creek, both flowing into the Queen River.

This discovery caused a rush, on a limited scale certainly, but still a rush. The blazed line of the prospectors was turned into a kind of track, the work being performed by a man named George Meredith, who was employed by tho Government. [George Meredith story of how this track came to be will be given in our next issue.—ED.] The track was named after him (Meredith track), and many a curse, deep and terrible, had poor Meredith to bear on account of it; but he was not to blame. However, the track was a demon. Along it the diggers had to pack their supplies, the entire distance of Everett’s and Howard’s creeks being (approximately) twenty miles from Strahan.

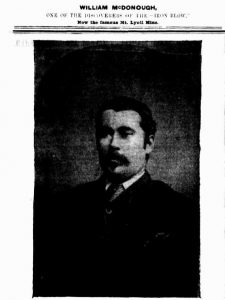

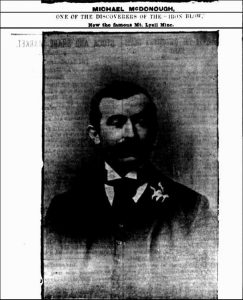

Among others who came to this rush were two brothers, known as the Cooney Bros., but whose real names were William and Michael McDonough, and one named Stephen Karlson. These men, not finding anything satisfactory in the then known creeks, determined to find a new creek for themselves, and with that object in view they crossed the Queen River, and taking an easterly course direct for the mountains. now distant about two miles, they mounted the long steep spur that separates the fall of the Queen River from that of the King, emerging on open country, they at length reached the top of the divide, when a wildly grand panorama lay before the wondering gaze of the astonished prospectors. Descriptive landscape painting is out of place here, worthy and rich in material as the subject is in this instance.

Descending the spur in the direction of a creek at its base, which they had already selected as being worth a trial, and when not more than 300yds. from it, their attention was arrested by an irregular shaped mass of peculiar dark-looking rock, jutting several feet out of the ground, and capped by a round patch of green scrub. Concluding to examine it more closely when time would permit, they descended to the creek, prospected it, and and obtained payable gold near where the Mount Lyell Co.’s huts now stand. The creek received the name of Cooney’s Creek.

Having pitched their camp on the narrow spur just where the old tailing dam can now be seen, they again directed their attention to the strange-looking mass of rock and decided to examine it more closely. They found it to be an immense outcrop of ironstone of dark blue colour, difficult to break and exceedingly heavy. Thinking that there might be something in it, they decided to peg off a prospecting area of fifty acres, which they accordingly did, taking good care to make the iron outcrop the very centre of their selection. And thus did William McDonough, Michael McDonough, and Stephen Karlson become the first and absolute possessors of what now the Mount Lyell Mine. The dark mass of iron was what was afterwords known, as the famous Iron Blow, the beacon which indicated the presence of a formation almost unique in the history of mining, and which is certainly destined to astonish the world.

The Cooney Bros. and Karlson were the first white men who ever set foot on the Iron Blow (or, indeed, black men for that matter, for it is difficult to conceive how natives could exist, unless they could subsist on snakes and button grass), and therefore were its discoverers. [There are varying opinions upon this point, as will be noticed by careful readers of this, journal later on.—ED.] The Cooney Bros.’ practical connection with Mount Lyell almost ended with its discovery, they having sold one share to James Crotty and made an arrangement with one William Dixon (who at that time was engaged carrying-on his back supplies to the field for the prospectors and miners), to work the other share still held by them on conditions which the parties understood.

Prospecting was commenced on the outcrop. Gold was to be had anywhere on the fall of the spur in payable quantities, but of such an exceedingly fine character that it could not be easily saved. However, a system of boxes, with finely perforated hoppers and with blankets, were brought into requisition, which acted fairly well, and sluicing operations were carried on with fair results, the material operated on being principally the waste from the iron outcrop, the bottom consisting of solid iron pyrites, streaked with tinges of copper.

The little party had at this time the most disheartening work to perform. All their supplies, including pit-saws, crosscuts, crowbars, blasting materials blacksmith’s and carpenter’s tools, had to be packed over Meredith’s track, a distance of 22 miles—as damnable a track as the combined ingenuity of nature and man could devise. Provisions were bad and expensive, and the winter of 1885 was abnormally severe.

There was, however, a gleam of hope for the future. Soon after the rush at Lynch’s Creek, a gold-bearing quartz lode was discovered, which was considered lured of sufficient, importance to induce the Government to make a road to the mine now owned by the King River Company. This mine was at Lynch’s Creek, the company named having been formed by the Hobart syndicate when Lynch reported to them the discovery of payable gold. The new road was being vigorously pushed on, and when completed a distance of 15 miles from Strahan, branch stores were erected at this point, and a track cut from there to connect Howard’s Plain with the Government road. This was a great boon to Mount Lyell, as it brought, the supplies of the men there working to within fourteen miles of them.

Sluicing operations were now continued with the object of running the gold to its source in the iron, the prospectors by this time being perfectly satisfied as to its origin.

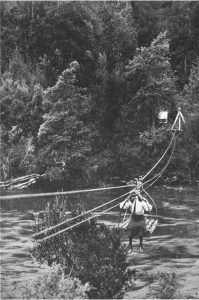

Early prospectors at the Iron Blow, 1884. Source: ABC

As the work progressed up the spur, the heavy iron boulders became more and more troublesome, until at length the party found it required more strength to carry on the work successfully, the result being that three new partner were admitted on easy terms, viz., Charles Karlson, Allan Karlson, and F. O. Henry, thus increasing the number of shareholders to six. Soon after this the Government road was completed to Lynch’s Creek, and stores wore erected there. This was another boon which the Mount Lyell party took early advantage of, by cutting a track along the Queen River to the stores, now only eight miles distant. At this time the party could make but slow progress, owing to the nature of the material to be shifted, consisting principally of blocks and boulders of iron of enormous weight, many of which had to be shot. Still sufficient gold was obtained lo defray all expenses.

At this juncture two of the Karlson Bros., Allan and Charley, becoming dissatisfied, sold out, and subsequently the third brother, Stephen, one of the original three prospectors, sold his share. The Government now decided to connect Lynch’s Creek with Mount Lyell, by means of a pack track round the foot-hills of Mount Owen. This rack was soon made available for man traffic, thus bringing Mount Lyell one mile nearer to the stores, the distance being now seven miles.

Labour was employed and prospecting vigorously carried on. The iron lode was found to occur on the eastern side of the great pyrites body. but its width could not as yet be ascertained. This was gradually encroached upon, until at last, about the 15th of June 1886, it was found to be exceedingly rich in gold.

The party next made their locations, first pegging off the area they were entitled to under the regulations—a reward for the discovery, namely, fifty-five acres. This was secured in three fifteen-acre blocks. They also pegged four ten-acre sections under lease, making a total of 85 acres. The pegging was completed and notices posted on the 15th June, 1886.

When they had secured the ground they lost no time in making their application, and duly reporting the discovery, thereby strictly complying with the requirements of the regulations. The news caused no inconsiderable excitement, A rush ensued, and the country was pegged off in all directions. Especially was this the case in a northerly and a southerly direction—the supposed course of the lode—where the locations extended for a distance of at least three miles, The Government of the colony sent their Geologist and Inspector of Mines, Mr. George Thureau to inspect and report on the new find. His report was of a most favourable character, and when issued to the public intensified the excitement to such a degree that a number of would-be [?] men formed a syndicate with the avowed object of jumping the Mount Lyell ground, on the plea that it was not the required distance from the nearest deposit – five miles as laid down in the Tasmanian gold regulations, before a reward claim can be granted. And now a most serious incident occurred, which very nearly ended in a tragedy.

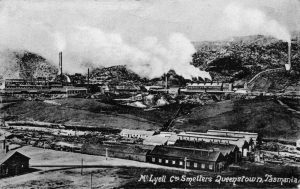

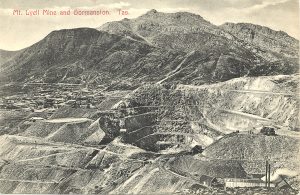

Mount Lyell mine. The open cut in the centre of the picture is what is left of the Irob Blow. Source: Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies.

To jump the Mount Lyell ground, it was first necessary to peg it, and for that purpose a man named Tom Jones, a billiard-marker from Mount Bischoff was employed. He (in company with another man) attempted to jump the claim at 1 o’clock one morning, by the aid of a lighted candle in a bottle. The light was observed by, one of prospectors moving in direction of the Iron Blow, and concluding such an extraordinary occurrence boded mischief, proceeded to intercept it. Picking up a revolver, mounting the hill and taking up an observant position, he saw the light moving towards where two of the corner pegs pegs stood and at once saw the game. Moving forward, the prospector got to the peg just as Jones arrived there with several pegs on his shoulder. He asked Jones, who was not a little astonished to find himself in company, what his business was, and what he was doing there at an unseemly hour. He replied:

“I came to peg some ground.”

“And why did you not come in daylight? This is a queer time to mark off a claim in a country like this”

“Oh. any time does!” replied Jones

“What ground do you intend to peg?”

“This ground.”

“But you are trespassing. This is our ground.”

“I came here to peg this ground, and I am am going to do it.” the jumper cheekily said.

“You cannot put a peg in this ground.”

“I am going to do it.”

“Very well, I warn you, before you do, to say your prayers, if your mother ever taught you any, for it will be your last peg.”

“Why?”

“Surely, man,” said the prospector, “you are not so stupid.” Producing a revolver, the prospector continued: “That ought to be sufficient caution. To be more explicit, do you want me to shoot you?”

Jones dropped the pegs.

After hearing the prospector’s opinion of his character, and admitting that he was paid to do the dirty work, Jones went straight back to Bischoff and swore an information against the prospector. The case was heard by Mr. Commissioner Crowther, at Strahan, the result being that the prospector was bound over to keep the peace for a year. Jones narrowly escaped finding a grave at Mount Lyell.

Stopping the pegging did not stop the jumping, the law taking the attempt for the deed. The services of a surveyor were obtained, a traverse survey was made, and Lynch’s discovery was found to be not quite five miles from the Iron Blow, although the prospector’s track by the Queen River was eight or nine miles and the route by Mount Owen seven miles.

The case was heard at Bischoff before Mr. Commissioner Belstead, Secretary of Mines. The prospectors won mainly on the evidence of Mr. Thureau. Government Geologist, who described the Mount Lyell discovery as being altogether unique, and consequently quite dissimilar to Lynch’s discovery, or any other that ever come under his notice, his experience being world-wide.

And thus did the Mount Lyell prospectors, on what, was nothing better than a quibble, almost lose the reward of long years of most persistent and unremitting toil enduring and surmounting hardships and difficulties in a country deserted by almost all but themselves—a country treacherous and inhospitable. the very appearance of which was enough to make the hardiest and most adventurous man pause before challenging the dangers of its tangled and well-nigh impenetrable forests.

The calling of the prospector is a most laudable and honorable one. He goes forth in the face of all dangers to extract the hidden secrets of nature, competing with no one for a livelihood. He extracts treasure from the hills, creates wealth, and turns the fastness of the mountains and the silence of the forest into busy scenes of industry. A public benefactor who has played an important part in the history of Australia, the mining prospector deserves the protection of his Government and the sympathy and support of every honorable man.

A keen appreciation of the terrible injustice the Mount Lyell prospectors almost suffered should induce those who have the manipulation of our mining laws to minimise, as far as possible, the chances for the repetition of such cases. The law should give the human shark no quarter.

John Henry, brother to F. O. Henry; William Ritchie, solicitor, of Launceston; Lindsay Tulloch, of Launceston; and John Powell, of Don, Tasmania, having mostly secured the Karlson Brothers’ interest, and thereby become shareholders, a meeting was held, when it was decided to form a company of 180 shares. Twenty of these shares were placed in trust as capital, and a certain portion ordered to be sold at £750 per share The property was invested in a trust, James Crotty and F. O. Henry being appointed trustees. A committee, consisting of John Henry, John Powell, George Horne and others, was also appointed.

Here the old prospectors’ reign ceased, and troubles began. but the mine was always a grand property. It paid the prospectors with a sluice-box. They obtained five or six hundred ounces of gold, although they did not, with their crude appliances, save one ounce of the fine metal in every 10. The battery that was erected should have paid, and paid well. F. O. Henry and James Crotty resigned their trusteeship, and William Ritchie. and either Lindsay Tulloch or George Horne were appointed in their stead. A system of tunnelling was being carried out on the mine, specimens of which still remain. The pack track from Lynch’s Creek was now completed, so that horses could get to the mine.

About this time the number of share in the company was increased from 180 to 1800, and subsequently, at a meeting of shareholders held at Launceston, the Mount Lyell Gold Mining Company, No Liability, was formed, with a capital of £9000 in 1800 shares of 10s each, all uncalled. Robert Carter was appointed manager, together with seven directors, all of whose names do not occur just now; but the following were amongst the number : George Horne. John Powell, James Crotty, and John Henry.

The ancient history of the Mount Lyell Mine is now written. What has occurred since the formation of the No Liability Company is, comparatively speaking, modern, and can be readily ascertained. That company was not a success, which was clearly not the fault of the mine.

The King River Company, whose history is closely connected with Mount Lyell, was a disastrous failure. This company deserved a better fate; it was plucky and honorable and a credit to Tasmania. Soon after Mr. Lynch (a good and honorable man) discovered payable quartz, he left the company’s service, and was succeeded by a man named Marsh, who gained the entire confidence of the directors, but the result of his management was not satisfactory to them.

[The history of the King River Company will appear next week,—ED.]

The present Mount Lyell Company has been too short a time in existence to give room for comment. It is pursuing a vigorous policy, which time will test.

If you like the content at Apple Isle Prospector, feel free to get in contact, or leave a comment. If you enjoyed this article, then let others know by sharing it on Facebook or liking our Facebook or Twitter pages: